CPL (Categorical Programming Language) is a programming language designed based on concepts from category theory. In CPL, what are typically referred to as “data types” and “functions” in conventional programming languages are instead treated as “objects” and “morphisms” (or “arrows”) in category theory.

| Set Theory | Functional Programming | CPL |

|---|---|---|

| Set | Data Type | Object |

| Mapping | Function | Morphism |

left object (initial structure) and

right object (terminal structure)For optimal understanding, familiarity with the following:

No prior knowledge of category theory is required. Through this tutorial, you’ll learn both CPL usage and fundamental category theory concepts.

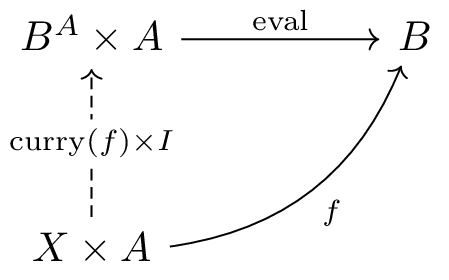

left objects and

right objects, and the concept of duality in category

theoryThe CPL REPL (Read-Eval-Print Loop) supports the following commands. This section provides only an overview, with detailed usage examples to be learned through practical application.

edit: Enters multi-line editing mode.

Use this for defining data types. End editing mode by entering semicolon

(;)show <expression>: Displays the

type (domain and codomain) of an morphism (function)show object <functor>: Displays

detailed information about an object (data type)show function <function>:

Displays the type of a factorizer (higher-order function) or

user-defined functionlet <name> = <expression>:

Defines an morphism by assigning it a namelet <name>(<arguments>) = <expression>:

Defines an morphism with parameterssimp <expression>: Simplifies

(computes) the given expressionsimp full <expression>: Fully

simplifies the expression (use when simp alone cannot

complete simplification)it: Refers to the result from the

previous computationload <filename>: Loads

definitions from a filehelp: Displays help informationexit: Exits the CPL environmentUpon startup, the interface appears as follows:

Categorical Programming Language (Haskell version)

version 0.1.0

Type help for help

cpl>CPL has no built-in data types, and all data types must be explicitly defined.

Since every operation requires the terminal object—corresponding to the unit type in other functional programming languages—we begin by defining this fundamental concept.

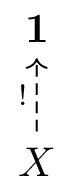

In category theory, a terminal object 1

is defined as “an object such that for every object X,

there is exactly one morphism from X to 1.” It

serves as an “endpoint” representing an object with no information (or

containing only one value). The unique morphism is written as

!.

Visually, this corresponds to the following situation:

Correspondences to programming concepts:

() type (unit type)void or unit types in other languagesNow, let’s define the terminal object in CPL. Using the

edit command, enter multi-line editing mode, input your

data type definition, and exit multi-line editing mode by entering

semicolon ;.

cpl> edit

| right object 1 with !

| end object;

right object 1 definedThe output “right object 1 defined” confirms that the

terminal object 1 has been successfully defined.

Detailed information about a defined object can be viewed using

show object.

cpl> show object 1

right object 1

- natural transformations:

- factorizer:

----------

!: *a -> 1

- equations:

(RFEQ): 1=!

(RCEQ): g=!

- unconditioned: yes

- productive: ()When object 1 is defined, a special morphism ! is also

defined from any object to the terminal object.

The show command can also be used to display the

morphism’s type (domain and codomain). Here, *a is a

variable representing an object, so this represents an morphism from any

object to the terminal object 1.

cpl> show !

!

: *a -> 1Next, we’ll define the product. The product combines two objects into a single object.

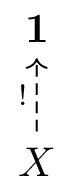

In category theory, the product A × B

(prod(a,b) in CPL) is defined as “an object that preserves

the information of both objects A and B.” It

satisfies the following properties:

π₁: A × B → A and

π₂: A × B → BX with morphisms f: X → A

and g: X → B to A and B

respectively, there exists a unique morphism

⟨f,g⟩: X → A × B such that π₁ ∘ ⟨f,g⟩ = f and

π₂ ∘ ⟨f,g⟩ = g (this kind of property is referred to as the

universal property).Visually represented as a diagram:

Correspondences with programming concepts:

(a, b) type (tuple)Now, let’s define the product in CPL:

cpl> edit

| right object prod(a,b) with pair is

| pi1: prod -> a

| pi2: prod -> b

| end object;

right object prod(+,+) defined(Note in the definition of pi1 and pi2 that

the object prod we’re defining now lacks arguments. The

mearning is “Among all x equipped with

x -> a and x -> b, we define the most

general x as prod(a,b),” but reusing the name

prod instead of introducing a new name x)

Unlike in the case of terminal objects, the product

prod(a,b) is an object that takes parameters, and the

resulting definition displays as prod(+,+). The

+ indicates covariance, and we can see that

prod takes two arguments and is covariant with respect to

both arguments. Use show object to display detailed

information.

cpl> show object prod

right object prod(+,+)

- natural transformations:

pi1: prod(*a,*b) -> *a

pi2: prod(*a,*b) -> *b

- factorizer:

f0: *a -> *b f1: *a -> *c

------------------------------

pair(f0,f1): *a -> prod(*b,*c)

- equations:

(REQ1): pi1.pair(f0,f1)=f0

(REQ2): pi2.pair(f0,f1)=f1

(RFEQ): prod(f0,f1)=pair(f0.pi1,f1.pi2)

(RCEQ): pi1.g=f0 & pi2.g=f1 => g=pair(f0,f1)

- unconditioned: yes

- productive: (yes,yes)Unlike terminal objects, in the case of products, both projection

morphisms pi1 and pi2 are defined

simultaneously (you can also check their types using the

show command).

Additionally, a function (factorizer) pair is also

defined, which constructs pair(f,g): a -> prod(b,c) from

f: a -> b and g: a -> c. The morphism

previously written as ⟨f,g⟩ is now written as

pair(f,g) in this definition of products in CPL. The

factorizer pair itself is not an morphism and cannot be

displayed using show; instead, use

show function to display its type.

cpl> show function pair

f0: *a -> *b f1: *a -> *c

------------------------------

pair(f0,f1): *a -> prod(*b,*c)Furthermore, while prod maps objects a and

b to the object prod(a,b), it also maps

morphisms f: a -> c and g: b -> d to

prod(a,b) -> prod(b,d). In category theory, a

functor maps objects to objects and morphisms between

objects to morphisms between mapped objects. Using

show function prod, you can verify the type of

prod’s action on morphisms.

cpl> show function prod

f0: *a -> *c f1: *b -> *d

---------------------------------------

prod(f0,f1): prod(*a,*b) -> prod(*c,*d)Furthermore, examining equations reveals that the

following four equalities hold. Here, the . notation

represents morphism composition, meaning

g.f means “first apply f, then apply

g” (corresponding to the mathematical notation

g ∘ f).

pi1.pair(f0,f1)=f0

pi2.pair(f0,f1)=f1

prod(f0,f1)=pair(f0.pi1,f1.pi2)

prod in terms of pair and

pi1, pi2)pi1.g=f0 & pi2.g=f1 => g=pair(f0,f1)

g satisfies the same conditions as

pair(f0,f1), then g=pair(f0,f1), i.e.,

pair(f0,f1) is unique)Next, we define the exponential object, which is a structure for treating functions as values.

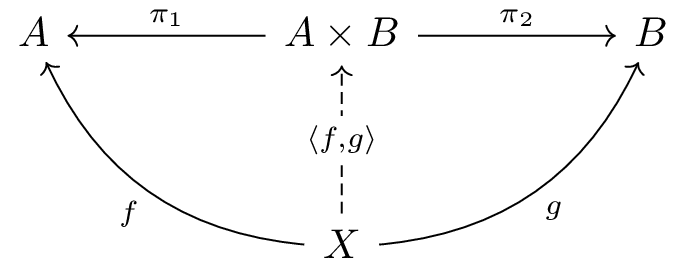

The exponential object Bᴬ (denoted as

exp(a,b) in CPL) represents “the object that encodes all

morphisms from A to B.” It possesses the

following properties:

eval: Bᴬ × A → B exists,

allowing functions to be applied to values

eval here, in functional programming

contexts, apply would be a more natural name)f: X × A → B, there exists a unique

curried morphism curry(f): X → Bᴬ satisfying

eval ∘ (curry(f) × I) = f

I: A → A represents the identity morphism, and

× denotes the product morphism operation)Visualized as a diagram, it appears as follows:

Why Is the Exponential Object Called a “Function Space”? Let’s consider this concretely in the context of the category of sets.

Bᴬ is the set

{f | f: A → B} of functions itself.eval(f, a) = f(a). In other words, it performs the

operation of “taking a pair of a function f and its

argument a, and returning the result of applying

f to a.”f: X × A → B, curry(f)(x) returns the function

a ↦ f(x, a). In other words, currying transforms a

two-argument function into a one-argument function that returns another

function — this is precisely the operation of converting a function into

a function that returns functions.X × A → B are in one-to-one correspondence with functions

from X → Bᴬ” — is what uniquely characterizes

Bᴬ as a function space. This correspondence is exactly the

relationship between currying and function application in

programming.Correspondences with programming concepts:

a -> b type (function type)A category equipped with the terminal object, product objects, and exponential objects is called a Cartesian Closed Category, which forms the theoretical foundation for lambda calculus and functional programming.

Now, let’s define the exponential object in CPL:

cpl> edit

| right object exp(a,b) with curry is

| eval: prod(exp,a) -> b

| end object;

right object exp(-,+) definedWe can display detailed information using

show object:

cpl> show object exp

right object exp(-,+)

- natural transformations:

eval: prod(exp(*a,*b),*a) -> *b

- factorizer:

f0: prod(*a,*b) -> *c

---------------------------

curry(f0): *a -> exp(*b,*c)

- equations:

(REQ1): eval.prod(curry(f0),I)=f0

(RFEQ): exp(f0,f1)=curry(f1.eval.prod(I,f0))

(RCEQ): eval.prod(g,I)=f0 => g=curry(f0)

- unconditioned: yes

- productive: (no,no)We can see that eval for function application,

curry for currying, and the conditions for an exponential

object in category theory are all defined.

Let’s examine how the functor exp operates on morphisms

using show function:

cpl> show function exp

f0: *c -> *a f1: *b -> *d

------------------------------------

exp(f0,f1): exp(*a,*b) -> exp(*c,*d)Note the directionality of the argument morphisms, and how the

parameters of exp change from domain to codomain in the

result:

f0 is a morphism from *c to

*a, but the parameter changes direction from

*a to *c in the resultf1 is a morphism from *b to

*d, and the direction of the parameter is the same, from

*b to *dThis indicates that exp is a contravariant functor with

respect to the first argument and a covariant functor with respect to

the second argument. The notation exp(-,+) used during

definition and in show object exp is a concise

representation of this property.

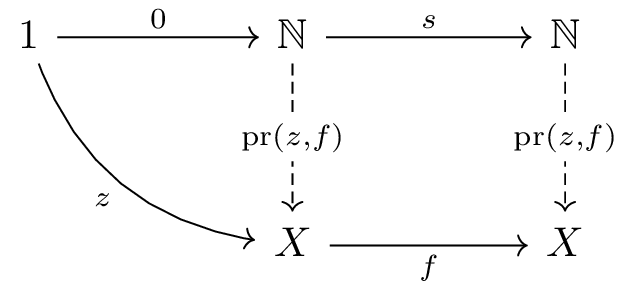

A natural numbers object is an inductively defined structure characterized by the number 0 and the successor function.

The natural numbers object ℕ is uniquely characterized

by the following elements:

0: 1 → ℕ (the initial value)s: ℕ → ℕ (also denoted as

succ, the function that increments by 1)X and morphisms z: 1 → X

and f: X → X, there exists a unique morphism

pr(z,f): ℕ → X defined recursively such that

pr(z,f) ∘ 0 = z and

pr(z,f) ∘ s = f ∘ pr(z,f)This pr operation corresponds to mathematical

induction and serves as the fundamental method for defining

functions over the natural numbers.

Visualized graphically, this structure appears as follows:

Please note the direction of the arrows. Whereas in the terminal objects, products, and exponential objects we have handled so far, there existed a unique morphism with that object as its codomain, in the case of the natural numbers object, conversely, there exists a unique morphism with that object as its domain.

Correspondences to programming concepts:

The definition of natural numbers according to Peano’s axioms

Equivalent to Haskell data types such as:

data Nat = Zero | Succ NatRecursive computations (folding)

Now, let’s define the natural numbers object in CPL. While we have

previously defined objects as right objects when there

exists a unique morphism with that object as their codomain, we

now define the natural numbers object as left object as

there exists a unique morphism with that object as their

domain:

cpl> edit

| left object nat with pr is

| 0: 1 -> nat

| s: nat -> nat

| end object;

left object nat definedTo display the defined information, use

show object nat:

cpl> show object nat

left object nat

- natural transformations:

0: 1 -> nat

s: nat -> nat

- factorizer:

f0: 1 -> *a f1: *a -> *a

-------------------------

pr(f0,f1): nat -> *a

- equations:

(LEQ1): pr(f0,f1).0=f0

(LEQ2): pr(f0,f1).s=f1.pr(f0,f1)

(LFEQ): nat=pr(0,s)

(LCEQ): g.0=f0 & g.s=f1.g => g=pr(f0,f1)

- unconditioned: no

- productive: ()Here, 0 and s represent the zero and

successor functions respectively, while pr corresponds to

mathematical induction, along with the conditions they must satisfy.

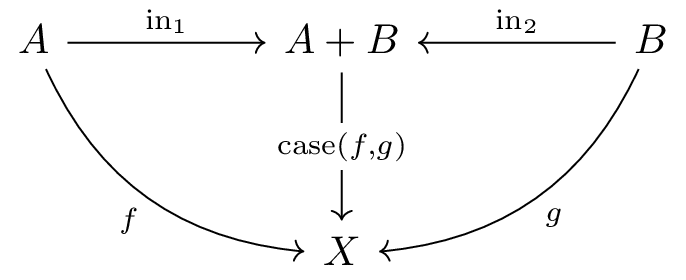

The coproduct is a structure representing “either-or,” serving as the dual concept to the direct product.

The coproduct A + B (denoted as coprod(a,b)

in CPL) is an object that can hold one of two values, either from object

A or B:

in₁: A → A + B and

in₂: B → A + B (which “inject” values into the

coproduct)X and morphisms f: A → X

and g: B → X, there exists a unique morphism

case(f,g): A + B → X that combines them case-by-case,

satisfying case(f,g) ∘ in₁ = f and

case(f,g) ∘ in₂ = gThis is the dual concept of the product, obtained by “reversing the arrow,” and serves as a good example of symmetry in category theory.

Visualized graphically, it appears as follows: (Compare with the product diagram to verify that morphisms are reversed):

Correspondences to programming concepts:

Either a b typevariant types or other languages’ union

types with tagsNow let’s define the coproduct in CPL:

cpl> edit

| left object coprod(a,b) with case is

| in1: a -> coprod

| in2: b -> coprod

| end object;

left object coprod(+,+) definedcpl> show object coprod

left object coprod(+,+)

- natural transformations:

in1: *a -> coprod(*a,*b)

in2: *b -> coprod(*a,*b)

- factorizer:

f0: *b -> *a f1: *c -> *a

--------------------------------

case(f0,f1): coprod(*b,*c) -> *a

- equations:

(LEQ1): case(f0,f1).in1=f0

(LEQ2): case(f0,f1).in2=f1

(LFEQ): coprod(f0,f1)=case(in1.f0,in2.f1)

(LCEQ): g.in1=f0 & g.in2=f1 => g=case(f0,f1)

- unconditioned: yes

- productive: (no,no)The show command can be used to display the types of

morphisms (their domains and codomains).

cpl> show pair(pi2,eval)

pair(pi2,eval)

: prod(exp(*a,*b),*a) -> prod(*a,*b)Here, *a and *b are variable ranging over

objects, and the morphism actually denotes families of morphisms with

varying types (domains and codomains). When these families satisfy

certain conditions, they are called natural

transformations, which correspond to polymorphic

functions in typical functional programming languages.

In the above example, pair(pi2,eval) is an morphism that

works for any objects *a and *b, and can be

viewed as a natural transformation from the functor

F(*a,*b) = prod(exp(*a,*b),*a) to the functor

G(*a,*b) = prod(*a,*b).

The . symbol appearing in the equations above refers to

fundamental operations on morphisms, which we will now review.

. represents morphism composition.

Given morphisms f: A → B and g: B → C, the

composed morphism g.f: A → C is the morphism that “first

applies f, then applies g”. This corresponds

to the mathematical notation g ∘ f (the Unicode symbol

∘ is also usable in CPL).

For example, we can represent natural numbers by composing the

successor function s: nat → nat with the zero

0: 1 → nat:

cpl> show s.0

s.0

: 1 -> nat

cpl> show s.s.s.0

s.s.s.0

: 1 -> nats.s.s.0 represents the “morphism obtained by composing

s (successor function) three times with 0”,

which corresponds to the natural number 3. Similarly,

s.s.0 represents 2, and s.0

represents 1.

The identity morphism I is the

“do-nothing” morphism, with I: A → A existing for any

object A:

cpl> show I

I

: *a -> *aAn identity morphism satisfies f.I = f and

I.f = f. While it may seem trivial at first glance, we

frequently use it in conjunction with functors to “transform only one of

the components while leaving the other unchanged”:

cpl> show prod(s, I)

prod(s,I)

: prod(nat,*a) -> prod(nat,*a)Here, prod(s, I) represents the morphism that “applies

s to the first component of the product while leaving the

second component unchanged.”

The let command allows us to assign names to morphisms,

enabling subsequent reference by name. This enables us to construct

complex morphisms step by step.

As our first example, let’s define the natural number addition

add: prod(nat, nat) → nat. This would be a function

typically written as follows:

add 0 y = y

add (x + 1) y = add x y + 1In CPL, we express this using primitive recursion pr

combined with currying curry. Let’s break it down step by

step.

Strategy: We want to use primitive recursion

pr on the first argument, but

pr(f0, f1): nat → X can only define unary morphisms.

Therefore, we curry the second argument by

encapsulating it within the exponential object.

Curried addition add':

add': nat → exp(nat, nat) — An morphism that takes a

natural number n and returns a “function that adds

n”pr(f0, f1)f0 = curry(pi2) (zero case):

add'(0) returns “the function that adds 0” = the

identity functionpi2: prod(1, nat) → nat is an morphism that extracts

the second component of a product, which here functions as “discarding

the first component (the unique value of the terminal object) while

returning the second argument unchanged”curry(pi2): 1 → exp(nat, nat) serves as the base case

for the zero casef1 = curry(s.eval) (successor

case):

add'(n+1) returns “a function that applies

s to the result of add'(n)”eval: prod(exp(nat,nat), nat) → nat represents function

applications.eval: prod(exp(nat,nat), nat) → nat performs

“function application followed by taking the successor”curry(s.eval): exp(nat,nat) → exp(nat,nat) represents

the recursive stepUncurrying: Revert

add' = pr(curry(pi2), curry(s.eval)) back to

eval and prod:

prod(add', I): prod(nat, nat) → prod(exp(nat,nat), nat)

— Applies add' to the first argumenteval.prod(add', I): prod(nat, nat) → nat — Applies the

resulting function to the second argumentPutting it all together:

cpl> let add=eval.prod(pr(curry(pi2), curry(s.eval)), I)

add : prod(nat,nat) -> nat definedIn the let construct, we can also define morphisms with

parameters.

cpl> let uncurry(f) = eval . prod(f, I)

f: *a -> exp(*b,*c)

-----------------------------

uncurry(f): prod(*a,*b) -> *cIn CPL, computation is performed through simplification of morphism

expressions using the simp command. Let’s simplify an

morphism using our previously defined addition function

add.

cpl> simp add.pair(s.s.0, s.0)

s.s.s.0

: 1 -> natThe result s.s.s.0 represents applying the successor

function s three times, corresponding to the natural number

3. This demonstrates the calculation 2 + 1 = 3.

Similar to addition, let’s define and compute multiplication and factorial.

Multiplication

mult: prod(nat, nat) → nat can be defined using the same

pattern as addition (currying + primitive recursion + uncurrying):

cpl> let mult=eval.prod(pr(curry(0.!), curry(add.pair(eval, pi2))), I)

mult : prod(nat,nat) -> natThe differences from add lie only in the zero case and

the recursive step:

curry(0.!) —

0 × y = 0 (0.! is an morphism that returns

zero regardless of input)curry(add.pair(eval, pi2)) —

(n+1) × y = n × y + y (adds the recursive result

eval to y itself pi2)Factorial fact: nat → nat uses a

slightly different approach. It carries the state of

prod(nat, nat) (a pair of accumulator and counter) using

pr:

cpl> let fact=pi1.pr(pair(s.0,0), pair(mult.pair(s.pi2,pi1), s.pi2))

fact : nat -> nat definedpair(s.0, 0) —

(1, 0), i.e. “0! = 1, counter = 0”pair(mult.pair(s.pi2, pi1), s.pi2) — computes

(acc, k) to ((k+1) × acc, k+1)pi1 extracts the

accumulator value (the factorial result)Let’s compute it:

cpl> simp fact.s.s.s.s.0

s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.s.0

: 1 -> natSince s has been applied 24 times, we obtain the correct

result 4! = 24.

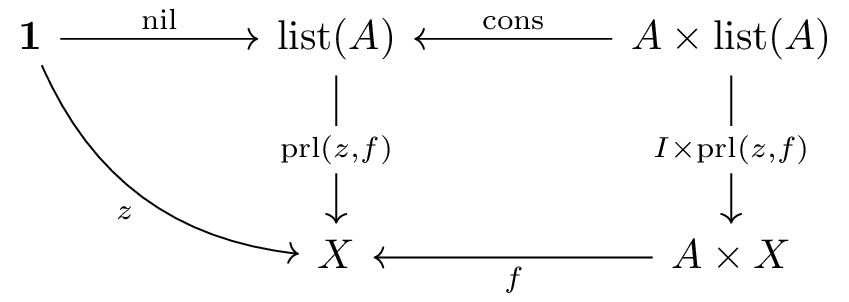

Next, we’ll define a list type—a data structure that’s very similar to natural numbers but slightly more complex.

Lists, like natural numbers, have an inductive structure, but they differ in that lists are parameterized by their element type:

nil: 1 → list(a)cons: a × list(a) → list(a) (adds an

element to the front)prl(z,f): list(a) → b for recursively processing

listsVisualized graphically:

This represents a classic example of an inductive data type that describes finite structures.

Correspondence with programming:

[a] type (lists)foldrNow let’s define lists in CPL:

cpl> edit

| left object list(p) with prl is

| nil: 1 -> list

| cons: prod(p,list) -> list

| end object;

left object list(+) definedcpl> show function list

f0: *a -> *b

------------------------------

list(f0): list(*a) -> list(*b)

cpl> show object list

left object list(+)

- natural transformations:

nil: 1 -> list(*a)

cons: prod(*a,list(*a)) -> list(*a)

- factorizer:

f0: 1 -> *a f1: prod(*b,*a) -> *a

----------------------------------

prl(f0,f1): list(*b) -> *a

- equations:

(LEQ1): prl(f0,f1).nil=f0

(LEQ2): prl(f0,f1).cons=f1.prod(I,prl(f0,f1))

(LFEQ): list(f0)=prl(nil,cons.prod(f0,I))

(LCEQ): g.nil=f0 & g.cons=f1.prod(I,g) => g=prl(f0,f1)

- unconditioned: no

- productive: (no)The list is also a parameterized object, that is, a functor. Let’s

examine its action on morphisms. In functional programming, this action

of the list functor on morphisms is often referred to as

map.

cpl> show function list

f0: *a -> *b

------------------------------

list(f0): list(*a) -> list(*b)Next, let’s express some familiar functions using the list type.

Concatenation (append):

cpl> let append = eval.prod(prl(curry(pi2), curry(cons.pair(pi1.pi1, eval.pair(pi2.pi1, pi2)))), I)

append : prod(list(*a),list(*a)) -> list(*a) definedReversal (reverse):

cpl> let reverse=prl(nil, append.pair(pi2, cons.pair(pi1, nil.!)))

reverse : list(*a) -> list(*a) definedhead / tail:

cpl> let hd = prl(in2, in1.pi1)

hd : list(*a) -> coprod(*a,1) defined

cpl> let tl = coprod(pi2,I).prl(in2, in1.prod(I, case(cons,nil)))

tl : list(*a) -> coprod(list(*a),1) definedWe’ve chosen hd / tl here because we want

to use these names when working with infinite lists later. In CPL, since

only total functions exist and no partial functions are allowed, the

codomain is a coproduct with 1 (equivalent to the

Maybe or Option types in other languages).

For convenience, we’ve also defined versions that lift the domain to

the coproduct with 1, allowing us to apply

head / tail to the results of these operations

again.

cpl> let hdp=case(hd,in2)

hdp : coprod(list(*a),1) -> coprod(*a,1) defined

cpl> let tlp = case(tl, in2)

tlp : coprod(list(*a),1) -> coprod(list(*a),1) definedSequential numbers [n-1, n-2, ..., 1, 0]:

cpl> let seq = pi2.pr(pair(0,nil), pair(s.pi1, cons))

seq : nat -> list(nat) definedNow, let’s perform some computations.

Some calculations require simp full instead of just

simp to proceed with reduction.

cpl> simp seq.s.s.s.0

cons.pair(s.pi1,cons).pair(s.pi1,cons).pair(0,nil)

: 1 -> list(nat)

cpl> simp full seq.s.s.s.0

cons.pair(s.s.0,cons.pair(s.0,cons.pair(0,nil)))

: 1 -> list(nat)While simp alone stops at an intermediate form,

simp full completes the full reduction. The result

cons.pair(s.s.0,cons.pair(s.0,cons.pair(0,nil))) represents

list notation in CPL. In other languages, this corresponds to the list

[2, 1, 0]:

| CPL Representation | Meaning |

|---|---|

nil |

[] (Empty list) |

cons.pair(x, xs) |

x : xs (Prepend x to the beginning of

xs) |

cons.pair(s.s.0, cons.pair(s.0, cons.pair(0, nil))) |

[2, 1, 0] |

Let’s examine the results of computing with other functions as well:

cpl> simp hdp.tl.seq.s.s.s.0

in1.s.0

: 1 -> coprod(nat,*a)Since seq.s.s.s.0 equals [2, 1, 0],

applying tl to remove the head yields [1, 0],

and then applying hdp to get the head results in

in1.s.0 (which equals Just 1).

cpl> simp full append.pair(seq.s.s.0, seq.s.s.s.0)

cons.pair(s.0,cons.pair(0,cons.pair(s.s.0,cons.pair(s.0,cons.pair(0,nil)))))

: 1 -> list(nat)

cpl> simp full reverse.it

cons.pair(0,cons.pair(s.0,cons.pair(s.s.0,cons.pair(0,cons.pair(s.0,nil.!)))))

: 1 -> list(nat)append.pair(seq.s.s.0, seq.s.s.s.0) concatenates

[1, 0] and [2, 1, 0] to form

[1, 0, 2, 1, 0], while reverse.it reverses

this to produce [0, 1, 2, 0, 1].

In the final example simp full reverse.it, we use

it to reference the result of the previous computation

(append.pair(seq.s.s.0, seq.s.s.s.0)). it is a

useful feature that automatically stores the result of the immediately

preceding simp command.

simp and simp fullCPL provides two reduction commands:

simp: Performs basic reduction. Fast

but may stop prematurelysimp full: Performs more thorough

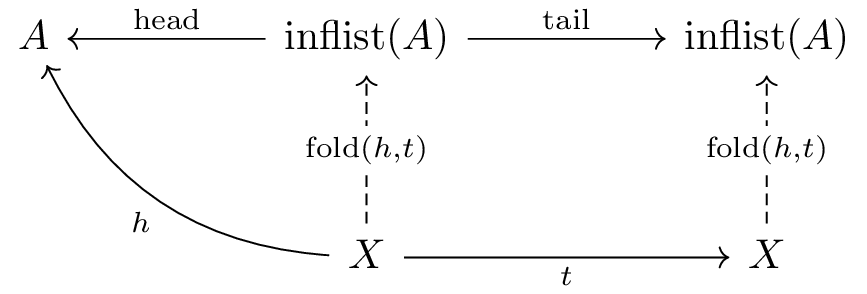

reduction. Use when a completely reduced form is requiredIn addition to finite data types like natural numbers and lists, we can also define data types for infinite lists.

Unlike finite lists, infinite lists are defined as a

right object. This is an example of a coinductive

data type:

head: inflist(a) → a (extracts the head element)tail: inflist(a) → inflist(a) (obtains the remaining

infinite list)fold(h,t): x → inflist(a) allows unfolding the infinite

list (note that while named fold, in modern functional

programming conventions this would more appropriately be called

unfold)While finite lists operate by “building up and then consuming,” infinite lists have the contrasting structure of “unfolding from state.”

Visualized graphically:

Corresponding to programming concepts:

unfoldNow let’s define an infinite list in CPL.

cpl> edit

| right object inflist(a) with fold is

| head: inflist -> a

| tail: inflist -> inflist

| end object;

right object inflist(+) definedcpl> show object inflist

right object inflist(+)

- natural transformations:

head: inflist(*a) -> *a

tail: inflist(*a) -> inflist(*a)

- factorizer:

f0: *a -> *b f1: *a -> *a

------------------------------

fold(f0,f1): *a -> inflist(*b)

- equations:

(REQ1): head.fold(f0,f1)=f0

(REQ2): tail.fold(f0,f1)=fold(f0,f1).f1

(RFEQ): inflist(f0)=fold(f0.head,tail)

(RCEQ): head.g=f0 & tail.g=g.f1 => g=fold(f0,f1)

- unconditioned: no

- productive: (no)Now, let’s define and compute with morphisms using infinite lists.

First, we create an ascending sequence 0, 1, 2, 3, …:

cpl> let incseq=fold(I,s).0

incseq : 1 -> inflist(nat) definedfold(I,s) represents the unfolding rule that “outputs

the current state as the head (I), then

applies s to the state to proceed.” Starting from the

initial state 0, this produces the infinite sequence 0, 1,

2, 3, …

cpl> simp head.incseq

0

: 1 -> nat

cpl> simp head.tail.tail.tail.incseq

s.s.s.0

: 1 -> natWe can extract the first element 0 using head, and the

fourth element 3 using head.tail.tail.tail.

Next, we define the alt function that alternates between

two infinite lists:

cpl> let alt=fold(head.pi1, pair(pi2, tail.pi1))

alt : prod(inflist(*a),inflist(*a)) -> inflist(*a) definedalt uses the product prod(inflist, inflist)

as its state, with head.pi1 outputting the head of the

first list, and pair(pi2, tail.pi1) swapping the roles of

the two lists (outputting the second list first, followed by the first

list’s tail).

cpl> let infseq=fold(I,I).0

infseq : 1 -> inflist(nat) defined

cpl> simp head.tail.tail.alt.pair(incseq, infseq)

s.0

: 1 -> natinfseq is a constant sequence 0, 0, 0, … The expression

alt.pair(incseq, infseq) produces an alternating sequence

0, 0, 1, 0, 2, 0, 3, … Therefore, the third element (index 2 starting

from 0) is s.0 (= 1).

When defining data types in CPL, there are two types of declarations:

left object and right object. This reflects

the important concept of duality in category

theory.

A right object is a structure based on

limits in category theory. Limits are characterized by

their property of being “defined by incoming morphisms

from other objects.”

1: The unique morphism !

from any object to 1prod(a,b): Creates morphism

pair(f,g): x -> prod(a,b) from two morphisms

f: x -> a and g: x -> bexp(a,b): Creates morphisms through

curryinginflist: Expands infinite structures

using foldA left object is a structure based on

colimits in category theory. Colimits are characterized

by their property of being “defined by outgoing

morphisms from this object to others.”

nat: Consumes (folds) natural numbers

defined recursively by prcoprod(a,b): Branches into two cases using

caselist: Folds recursive list structures using

prlGeneral guidelines:

left object (constructed recursively)right object (expanded corecursively)However, the symmetry between left and right in category theory is profound, and being able to experience this duality while using CPL is one of the language’s key features.

This left/right distinction corresponds to the following:

| CPL | Category Theory | Property |

|---|---|---|

| right object | Limit, Right adjoint, F-coalgebra | Unifies “incoming” morphisms via universal morphisms |

| left object | Colimit, Left adjoing, F-algebra | Unifies “outgoing” morphisms via couniversal morphisms |

In CPL, these concepts are treated symmetrically, allowing you to learn how category theory concepts are applied in practical programming.

Through this tutorial, you’ve learned both the basic usage of CPL and fundamental category theory concepts.

CPL usage:

edit,

show, let, simp, etc.)left object and right objectCategory theory concepts:

right object and left objectIn CPL, structures that would typically be “built-in” in other programming languages (such as numbers, lists, and functions) are all explicitly defined using category theory concepts. This results in:

To deepen your understanding of CPL, we recommend trying the following:

samples/ directory contains various program

examplesload “samples/examples.cpl”samples/ack.cpl)We hope this tutorial serves as your first introduction to the world of CPL and category theory. Happy programming!